South Sudan is the world’s newest country, having gained its independence in 2011. Sadly, in that short time it has become a study of a nation’s collapse.

South Sudan is the world’s newest country, having gained its independence in 2011. Sadly, in that short time it has become a study of a nation’s collapse.

Though South Sudan is oil-rich, pervasive corruption and nine years of tribal warfare have left it the world’s poorest country. Heavy inflation has critically reduced food production, leaving 7 million people on the edge of starvation. Almost 60% of the population are refugees of one category or another.

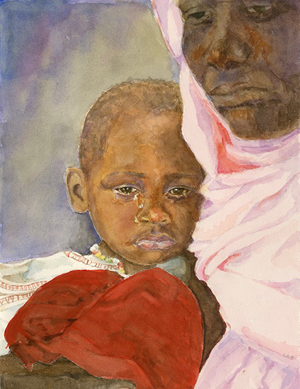

I will turn our attention to the widows of South Sudan. We know God’s eye is on the fatherless, so his compassion touches the widows who hold the fatherless. They are the ones left with babes in arms, with makeshift “homes” in the vast UN camps, with distress for their own safety, and grief for the losses which their children suffer.

The following analysis will reveal how widows suffer the most and in the worst ways.

Displacement

Flooding by the White Nile has left thousands of homes in knee-deep water. This has forced the people into homeless. But to flee where for shelter? Other villages have received hundreds of refugees already, and UN camps are overcrowded.

Fully 2 million people are Internally Displaced Persons (IDP). IDP translates into women carrying their few possessions, gleaning what food they can find, and sorrowing for the past day and for what awaits in the next. Over half of these refugees are children under 14.

Abuse

Women leave the confines of the UN camps at high risk. There, beyond the security of the camp, they face the danger of rape. In villages where there is no protection, raping takes place frequently and publicly—in front of children and in front of neighbors. These often result in death.

To exacerbate the crime, AIDS is widespread among the men, who, by raping, pass it to the widows. And in the worst irony of the atrocity, the shame of this brutality lies not upon the barbaric men but on the widows.

Infants and children

Disaster strikes these in three ways, each one almost invisible.

The number of children with kwashiorkor is in the hundreds of thousands. Kwashiorkor is a disease of protein deficiency in infants. That, in turn, results in under-developed brain tissue, which leads to lower IQ. The threat of this disease lies with malnutrition, a by-product of food scarcity.

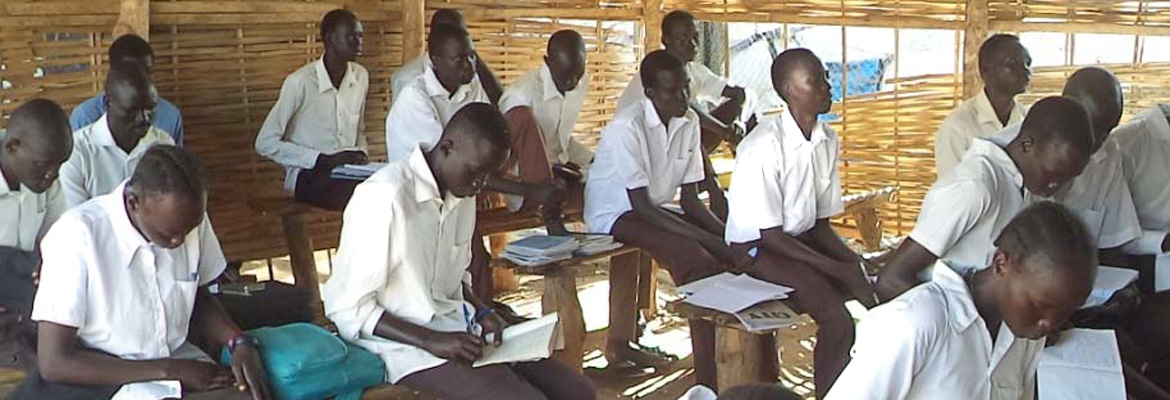

Education is a priority for their children, but life interrupts that, also. A convergence of hope and corruption hit schools recently. The United Kingdom gave thousands of books for schools to be distributed at no cost. They became available at many locations—for sale at the local market.

Children missing their childhood is an invisible loss. They will not have memories of playgrounds, of picnics with family, of reading books about other children. They will not go through the natural growth, the fun, the challenges of becoming a teenager. What is even worse, they will not know that they have missed these “normal” experiences.

Status of Women

Their “status” demands that they do manual labor, bear children, make a home. Their status permits sexual abuse on them, female genital mutilation, shameful acts perpetrated in front of their children. They do not have funds or means of travel to barter for food for their children.

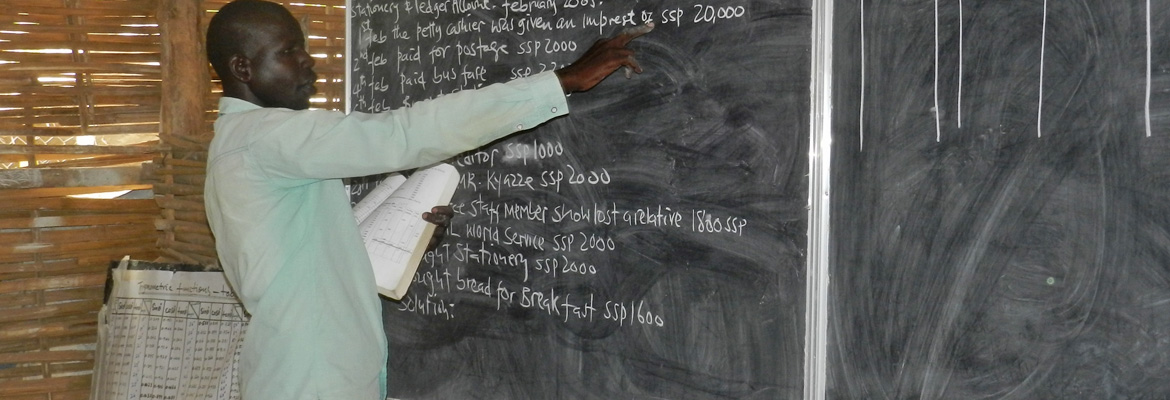

Literacy, always a path of hope, is about 45% in South Sudan, but for women, less than 28%. That level is usually below 8th grade.

That is why I say that widows suffer the most and in worst ways.

Any discussion of refugees leads to the hope of donor relief. For that, the donor looks for certain marks: familiarity with the circumstances, sympathy for the victims, and prospects for their future. Let me apply these criteria to South Sudan.

Familiarity with the circumstances:

It is a long way from anywhere to the airport in Juba. On arrival come warnings of danger. Then come the high prices, followed by neglected roads, checkpoints, tutorials in dealing with corruption, and shocking views of poverty and men with machine guns. It’s a long way to South Sudan, and it is easy to see why so few make the journey.

Sympathy for the cause:

In the reality of tribal warfare, sympathy means supporting either the Dinka or the Nuer. Or it means, who on the outside really cares?

Prospects for their future:

A leader from one of the Balkan nations recently expressed why he supported Ukrainian refugees over Africans: They look like us, they have degrees, they are leaders, they will return and rebuild. OK. I really don’t need to put those remarks into the context of South Sudanese widows, do I?

But they do have donor support. The supreme donor is God and his gift is passionate love and care for the widows and the fatherless. This is not an academic statement. The reality of this truth almost literally drenches them, bringing a hope that is almost palpable.

Within the generic grouping of them as “God’s Other Children,” many of them have moved under the shadow of his wings. They are sweetly trusting and ever faithful. These know that their cries are heard by their heavenly father and that they are counted as his beloved children.

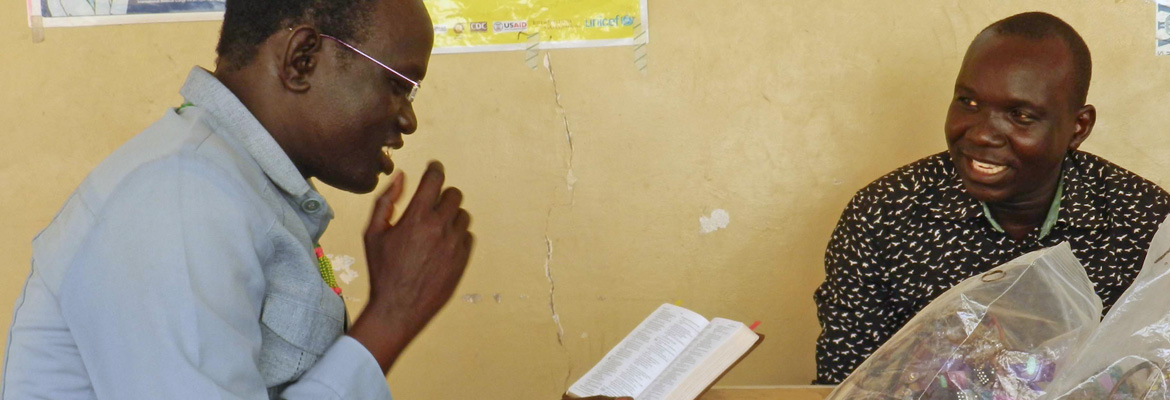

This drenching, this palpable assurance brings exuberant excitement. When they gather under a bamboo tree or a roof, and when the catechist has come and brought to them Bibles, and when he reads them reminders of God’s love and care, light shines!

The catechist could choose a text like Psalm 10. From it he would read how God does not forget the helpless, how he will lift up his hand to break the arm of the wicked. He hears the desire of the afflicted and listens to their cry. The Psalm tells them that God defends the fatherless and the oppressed, will bring justice, has grief and sorrow for them, and finally declares that no one will terrify them anymore. The worship this elicits is filled with extreme energy and joy. So I am told.

A friend and I were talking the other day about this Psalm and how we respond in our services—exhibiting our typical worship posture of hands in pocket, no expression on face, and certainly no perceptible movement. That’s because our trials and challenges bear no resemblance to the trials and horrors of these widows. And because we are so very reverent White people!

Not so for the widows of South Sudan. When they hear of God’s promises, that hope, those words of comfort and assurances—they enter the holy of holies, angels cheerlead them, the heavenly host is drowned out! The Spirit is alive in depths and ways we know not of. Their joy is more precious than gold, and sweeter also than honey from the honeycomb. All will be well. They know.

Do you think they keep their hands in pockets and no expression on their face? Can you imagine them with no movement? I think not.